The Earth Mover's Distance and Similarity of Histograms

Oftentimes we are interested in programmatically answering the question: how similar are two given objects of some kind, a prime example being the degree of similarity between two images. Nowadays, sophisticated techniques exist to accomplish this task, e.g., making use of neural networks and cleverly designed machine learning architectures. This approach requires an elaborate machine training process and large amounts of training data. There is also no guarantee that the trained model will generalize well to all previously unseen examples. A different approach that may be somewhat less powerful, but works consistently on any set of examples, is the introduction of a mathematical distance metric. For specific objects, various functions could play the role of a distance metric, so long as they are symmetric, non-negative and satisfy the triangle-inequality as described in the link above. A choice of a distance metric is appropriate if it adequately reflects our perception of similarity for the given objects. Interestingly, a similarity measure that works fairly well for image comparison is the so called earth mover’s distance.

Simple Histograms and Naive Distance

Before we discuss the earth mover’s distance, let’s define the objects we will be interested in comparing. For simplicity, we consider two one-dimensional, single channel images, say $h_1$ and $h_2$, of the same size. In particular, we assume that both $h_i$ (with $i=1,2$) are sequences of $n\in\mathbb{N}$ pixel values

\[h_1^{(1)},h_1^{(2)},...,h_1^{(n)}\in\mathbb{R}^+~\text{ and }~h_2^{(1)},h_2^{(2)},...,h_2^{(n)}\in\mathbb{R}^+,\]where $\mathbb{R}^+$ denotes positive real numbers. In this one-dimensional case we can think of the images $h_1$ and $h_2$ as two histograms with different distributions of weights $h^{(j)}$. Intuitively, a similarity comparison should be possible when both histograms have equal normalization. So, for convenience, we can agree to normalize both overall weights to one

\[\sum_{j=1}^n h_1^{(j)}=\sum_{j=1}^n h_2^{(j)}=1.\]It may be instructive to first consider why a naive notion of distance might be insufficient for determining similarity. Arguably, the Euclidean distance $E_{1,2}=\sqrt{(h_1-h_2)^2}$ (involving vector subtraction and multiplication) is the simplest one we might imagine. Clearly, this distance properly vanishes if $h_1$ and $h_2$ have the same weights, it is symmetric, and grows positive when $h_1$ and $h_2$ differ. However, if the weights of $h_2$ are shifted relatively to $h_1$, we want a proper distance measure to be aware of the amount of the shift and grow proportionally. Unfortunately, the Euclidean distance $E_{1,2}$ has no way of recognizing and accounting for similarities under a shift, and is therefore not the best choice. (We will see an explicit example below.) Let’s now consider a distance measure that does a better job.

Definition of Earth Mover’s Distance

Think of a histogram $h_i$ as a sequence of $n$ buckets arranged in a straight line, any two neighboring buckets having the same separation from each other. Imagine that each weight $j$ for $j=1,2,…,n$ denotes an amount of water filled into bucket $h_i^{(j)}$. Given a particular distribution of one gallon of water among the $n$ buckets $h_1$, we can characterize the similarity of $h_1$ to a different water distribution $h_2$ by the water amounts $f_{ab}$ which we have to move from bucket $h_1^{(a)}$ to bucket $h_1^{(b)}$ for all $a,b=1,2,…,n$ in order to transform $h_1$ into $h_2$. What does that mean in particular?

First of all, naturally the amount of water we move out of any bucket can either be zero, or positive

\[\label{pos}f_{ab}\geq0 ~ ~ ~, ~ ~ ~ 1\leq a,b\leq n.\tag{1}\]We can never move more water out of bucket $h_1^{(a)}$ than is there initially

\[\label{source}\sum_{b=1}^n f_{ab}\leq h_1^{(a)},\tag{2}\]and we should never move more water into bucket $h_1^{(b)}$ than is required to match the content of $h_2^{(b)}$

\[\label{sink}\sum_{a=1}^n f_{ab}\leq h_2^{(b)}.\tag{3}\]Finally, if we agree to denote by $f_{aa}$ the amount of water we keep in bucket $h_1^{(a)}$ without moving it anywhere else, the total amount of water redistributed by the operations $f_{ab}$ should equal one gallon

\[\label{norm}\sum_{a=1}^n \sum_{b=1}^n f_{ab}=1.\tag{4}\]Water is heavy, so it is clear that we are interested in moving as little of it as possible to transform $h_1$ into $h_2$. Additionally, if we must carry some water, we would always prefer to carry it only as far as necessary, without making redundant trips. Therefore, denoting the separation between buckets $h_1^{(a)}$ and $h_1^{(b)}$ by $d_{ab}$, we define the earth mover’s distance as

\[\label{EMD}\text{EMD}(h_1,h_2)\equiv\arg\min_F\left(\frac{\sum_{a=1}^n \sum_{b=1}^n d_{ab}f_{ab}}{\sum_{a=1}^n \sum_{b=1}^n f_{ab}}\right)=\arg\min_F\left(\sum_{a=1}^n \sum_{b=1}^n d_{ab}f_{ab}\right),\tag{5}\]meaning that we determine components $f_{ab}$ of the flow matrix $F$ such that the total flow weighted by separations $d_{ab}$ is minimized. The denominator conveniently simplified due to normalization $\eqref{norm}$.

So far, we only referred to $d_{ab}$ as the separation between buckets $h_1^{(a)}$ and $h_1^{(b)}$. Using the absolute value notation $|x|$, in our histogram case this is simply

\[\label{dab}d_{ab}\equiv |a-b|\tag{6}.\]However, it is important to keep in mind that in more complicated cases this separation can take on more intricate form, adapting EMD$(h_1,h_2)$ to the specifics of the new problem.

Note that, since the earth mover’s distance considers not just a pairwise difference but allows for the flow of water between any two buckets weighted by their separation, intuitively it is much better equipped to estimate the amount of similarity under a shift of weights than the Euclidean distance. (See the explicit example given at the end.)

Calculation of Earth Mover’s Distance

Constrained minimization problems such as $\eqref{EMD}$ under the requirements $(\ref{pos},\ref{source},\ref{sink},\ref{norm})$ fall under the category of linear programming; and, sure enough, we can use an off-the-shelf linear optimization solver to determine the optimal flow components $f_{ab}$. Linear programming is quite a non-trivial task, and is subject of extensive research by many brilliant scientists around the world — suggesting that being mere tourists in this area, we may want to settle with the off-the-shelf solver provided by professionals as our best tool of choice. On the other hand, out of curiosity we may want to explore a bit further.

Can we think of an algorithm that determines optimal flow components $f_{ab}$, given our special case of one dimensional histograms and the simplicity of $d_{ab}$? At least a potential greedy algorithm comes to mind: Starting from one end of the histogram and iterating inwards comparing water levels in buckets of $h_1$ and $h_2$ two at a time, we may choose to move the maximally allowed amount of excess water, yet not more than required, between buckets of closest separation, disregarding the possibility of moving same water to buckets which are further away. This strategy is motivated by large distance aversion, since carrying water to buckets that are further away is likely to increase the earth mover’s distance due to multiplication with larger values of $d_{ab}$.

A simple implementation of the above strategy in c++ looks as follows

#include <assert.h>

#include <algorithm>

#include <vector>

using namespace std;

vector<vector<double>> getFlow(vector<double> h1, vector<double> h2) {

assert(h1.size() == h2.size() && h1.size() > 0);

int i=0,j=1,n = h1.size(); // number of buckets in histogram

vector<vector<double>> F(n); // flow matrix to be determined

vector<double> dif(n);

for (int l = 0; l < n; l++) {

vector<double> row(n);

F[l] = row; // initialize rows of flow matrix to zero

F[l][l] = min(h1[l], h2[l]); // keep as much water in place as possible

dif[l] = h2[l] - h1[l]; // discrepancy of water levels

}

while (i + j < 2 * (n - 1)) {

if (dif[i] > 0. && dif[j] < 0.) { // move water from left to right

if (dif[i] <= -dif[j]) {

F[j][i] = dif[i];

dif[j] += dif[i];

dif[i] = 0.;

i++;

j = i + 1;

} else {

F[j][i] = -dif[j];

dif[i] += dif[j];

dif[j] = 0;

if (j < n - 1) {

j++;

} else {

i++;

j = i + 1;

}

}

} else if (dif[i]<0. && dif[j]>0.) { // move water from right to left

if (-dif[i] >= dif[j]) {

F[i][j] = dif[j];

dif[i] += dif[j];

dif[j] = 0.;

if (j < n - 1) {

j++;

} else {

i++;

j = i + 1;

}

} else {

F[i][j] = -dif[i];

dif[j] += dif[i];

dif[i] = 0.;

i++;

j = i + 1;

}

} else if (dif[i] == 0.) { // skip zero discrepancy bucket

i++;

j = i + 1;

} else { // advance if both buckets have lack or excess of water

if (j < n - 1) {

j++;

} else {

i++;

j = i + 1;

}

}

}

return F;

}The while loop repeats for at most n*(n-1)/2 iterations, which makes the code run in $\mathcal{O}(n^2)$ time. In contrast, a linear programming type approach, converted to the same counting, reportedly produces a result in roughly $\mathcal{O}(n^2\log^2n)$ time. This sounds encouraging; but is our attempt at a greedy solution any good? Let’s take a look at an explicit example.

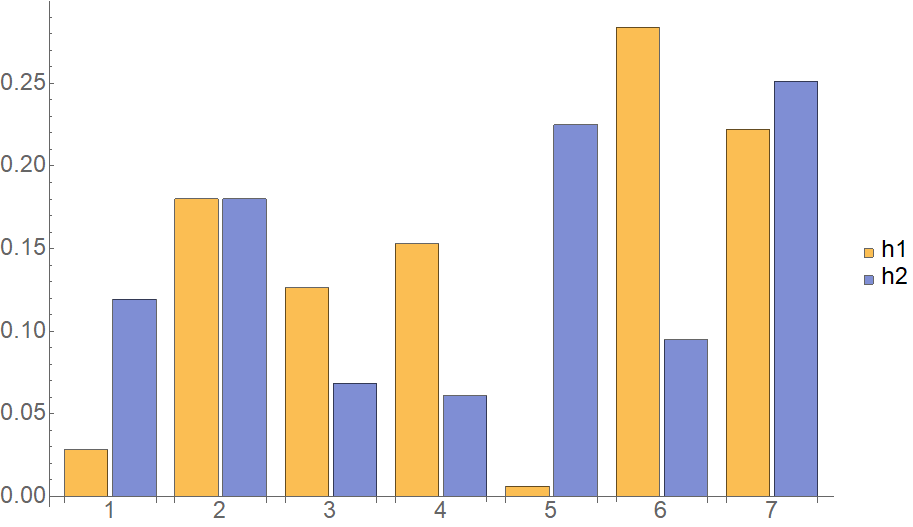

Take for instance the following two histograms as input

vector<double> h1{0.0283631,0.180109,0.126329 ,0.153043 ,0.00608183,0.283972 ,0.222101};

vector<double> h2{0.11945 ,0.180109,0.0683887,0.0609638,0.225002 ,0.0949184,0.251168};Side by side, these $h_1$ and $h_2$ look as follows:

We see that some water transport is necessary in order to transform $h_1$ into $h_2$.

First, let’s consider the optimal flow matrix generated by a linear programming solver:

\[F_{lp} = \left( \begin{smallmatrix} 0.0283631 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0.0470686 & 0.133041 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0.0372398 & 0.0326001 & 0.0564894 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0.00677813 & 0.0144685 & 0.0118993 & 0.0609638 & 0.0589331 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0.00608183 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0.159987 & 0.0949184 & 0.0290666 \\\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0.222101 \end{smallmatrix} \right)\]An interesting feature we can observe here, is that even though buckets $h_1^{(2)}$ and $h_2^{(2)}$ had the same amount of water $0.180109$ initially, the optimal solution still sent $0.0470686$ from $h_1^{(2)}$ to $h_1^{(1)}$ and later replenished the missing amount in $h_1^{(2)}$ from buckets $h_1^{(3)}$ and $h_1^{(4)}$.

Now, let’s take a look at the flow matrix generated by our greedy solution:

\[F_{g} = \left( \begin{smallmatrix} 0.0283631 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0 & 0.180109 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0.0579407 & 0 & 0.0683887 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0.0331459 & 0 & 0 & 0.0609638 & 0.0589331 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0.00608183 & 0 & 0 \\\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0.159987 & 0.0949184 & 0.0290666 \\\\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0.222101 \end{smallmatrix} \right)\]This matrix looks similar, but there are a few differences. In particular, since buckets $h_1^{(2)}$ and $h_2^{(2)}$ had the same amount of water initially, no water was sent from $h_1^{(2)}$ to $h_1^{(1)}$. In general, the main difference between the greedy solution and the optimal solution is that only excess water is ever moved by the greedy solution.

Conclusion

So our flow matrix $F_g$ did not match the optimal solution $F_{lp}$ exactly. Does this mean our calculation has failed? Not necessarily. After all, the flow matrix is only an ingredient. What we actually care about is the final value of the earth mover’s distance $\eqref{EMD}$. Curiously, it turns out that despite the apparent differences, both the optimal and greedy solutions lead to exactly the same EMD:

\[\sum_{a=1}^n \sum_{b=1}^n d_{ab}(f_{lp})_{ab} = \sum_{a=1}^n \sum_{b=1}^n d_{ab}(f_{g})_{ab},\]which amounts to $0.463306$ for the above example.

This is a generic feature of the one dimensional problem. Namely, carrying a load $L$ from $A$ to $B$, and then replenishing by carrying load $L$ from $C$ to $A$, is equivalent to carrying $L$ directly from $C$ to $B$ as long as the intermediate distances are fully additive. Which is just another way of saying that it is impossible to cut a corner when moving in a single spatial dimension, provided that we are being careful not to perform redundant jitter motions to begin with.

The computational simplifications in this special case of the earth mover’s distance are not particularly deep or profound, and we pieced it together in just a few lines above. However, simple does not necessarily mean useless, since the task of determining the similarity of two normalized one-dimensional histograms comes up relatively often. One never knows when a quick algorithm might come in handy!

Earth Mover’s Distance Under a Weight Shift

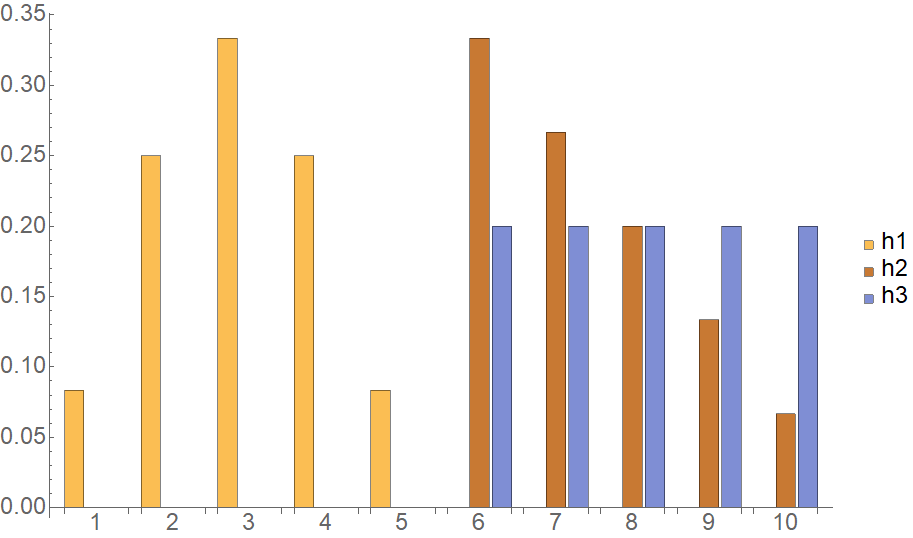

Our motivation for introducing the earth mover’s distance over the Euclidean distance was its ability to better recognize similarity when the weights of the two histograms being compared have a relative shift. To demonstrate this property explicitly, let’s consider the following three histograms

vector<double> h1{0.0833333, 0.25, 0.333333, 0.25, 0.0833333, 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.};

vector<double> h2{0., 0., 0., 0., 0., 0.333333, 0.266667, 0.2, 0.133333, 0.0666667};

vector<double> h3{0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2, 0.2};Side by side, these $h_1$, $h_2$ and $h_3$ look as follows:

Comparing $h_1$ with $h_2$ and $h_3$, intuitively we would classify $h_2$ as having larger similarity with $h_1$ (smaller distance), since it actually has a spike that is also located relatively closer to the spike of $h_1$ than the overall flat distribution of $h_3$. Do our two distance measure candidates capture this intuition?

The Euclidean distance results in

\[\sqrt{(h_1-h_2)^2}=0.703167~ ~ ~,~ ~ ~\sqrt{(h_1-h_3)^2}=0.67082~.\]So, unfortunately, the Euclidean distance erroneously suggests that $h_3$ is closer in similarity to $h_1$.

On the other hand, the earth mover’s distance returns

\[\text{EMD}(h_1,h_2)=4.33333~ ~ ~,~ ~ ~\text{EMD}(h_1,h_3)=5.0~.\]It correctly classifies $h_2$ as being closer in similarity to $h_1$, which makes the earth mover’s distance a much more useful similarity measure for this task compared to the Euclidean distance.